I could feel the upheaval as soon as I entered the room. My mom was nowhere to be seen, and my Nicaraguan host dad, Reynaldo, was shuffling around in the kitchen. It was early in the morning, and he was aimlessly pacing around. Eventually, he put away a rusty metal serving spoon, hanging it on a nail in the wall. He turned to grab a wooden bowl off the windowsill, stared at it, and put it on a different shelf. He didn’t seem to know what to do with himself.

I was new to most things in Nicaragua, but I knew for certain that my father was not the normal family cook. Although I had seen him in the kitchen several times, it was only to bring pichingas full of water, chopped firewood, and sacks full of lechuga inside for my mother.

My dad looked at me, gestured toward the steamy arroz and frijoles warming on the clay stove, and said, “Your mother is in town today for a routine doctors appointment. She made breakfast before she left this morning.”

Really? I thought to myself, She’s gone one day and my dad can’t make his own food? I knew men and women in Nicaragua were expected to fulfill certain roles in the household, but this seemed ridiculous. I finished eating my arroz and frijoles by myself and walked back to the bucket of water sitting on the wooden countertop. Normally, my mother would take away my dishes before I had a chance to wash them, but today I was on my own.

While I sipped on my warm coffee, I watched my dad roam around the house. Normally, he was out and about taking care of his plants and watching out for his animals. His expertise was running the farm and my mother’s expertise was keeping the household in order. In the six weeks I had been there, this had always made me uneasy. I wondered what opportunities my mother was missing out on and what talents she hadn’t yet discovered in herself. Did she ever wonder what else she could have done with her life?

After my dad, little brother, and a few farm hands had eaten their breakfast of rice and beans, they slipped on their work boots and headed down for the fields to start the day. I could tell my dad was relieved that breakfast was over. He looked tired already, and it was only eight thirty in the morning. Cooking is not that hard, I thought to myself. Why can’t these men just do more for themselves?

I snapped back to the present when I heard my dad’s voice. “Ana, tenemos algunas cosas para hacer.” We had a few things to do. He led me down to the long rows of lechuga, pepinos, basilica, and zanahorias in the garden. We needed to harvest, wash, and bunch the lettuce, cucumbers, basil, and carrots to sell in the mercado. Woah, I thought to myself, how on earth would my dad get all of this done without help? There was no way my dad could run an efficient farm if he was at the house all day.

I knew my mom didn’t do much down at the garden, but I attributed that to a lack of desire to do manual labor. It never crossed my mind that there would be other important things to take care of at the house, other than cooking. She also fed the goats, the pigs, the chickens, kept the path to our house clean, and cared for the guests that came for tours of the village. Neighbors depended on her for things too, and each morning she was in charge of the preschool in the center of town.

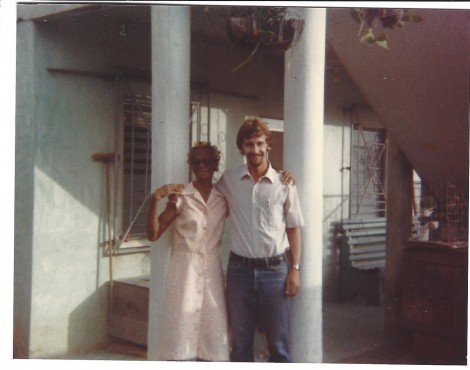

The next day, everything was back to normal. I was pleased to see my mother, Adriana, standing in the middle of the kitchen, sweeping the dirt floor and shooing chickens out of her way. She warmly greeted me with a hug and a kiss on the cheek, and made sure I had some café to start the day. I patiently sipped my gritty instant coffee while I waited for my breakfast. My brother, my father, and a few soltero neighbor men cycled through to get their warm rice and beans. My dad headed down to the farm early to make up for the work he missed the day before. He had stayed up at the house all morning and afternoon awaiting my mother’s arrival. Now that my mother was home, he seemed reassured that the house was in good hands.

The day before had felt very chaotic without my mother. I started to wonder how different things would have been without my dad. If my mother were doing her work in the house, who would work on the farm? Their children couldn’t, as they were either in school or married and living out of the house. Who would carry water to the house early in the morning or keep track of the cows and horses in the afternoon?

We needed to eat, but we could not grow all of it ourselves. With the small amount of vegetables my father sold on his farm, we could buy enough rice and beans to last a week. What if my dad got sick and no one could take care of the farm? Would we actually have food for the next week?

These thoughts stuck with me the next several days, until I realized: One cannot exist without the other. If my mother stopped her work, the family would be exhausted, and without my dad’s work, they would be hungry. I realized that I was the one being judgmental, not the Nicaraguan farm hands who expected my mother’s food each morning. In the United States, many people see cooking and cleaning for other people as something hired help does.

But my mother took pride in nourishing the people that took care of her and her family, just like my father worked tirelessly to put food on the table. For so long, I had mindlessly believed the things society had told me: Success meant having a reliable, well-paying, nine-to-five job. I had heard this for so long that I was blind to the joy my mother’s job brought her.

I admired my mother’s easy smile while she wiped down the wooden countertop in the kitchen. My father walked in with a pile of firewood on his shoulder and placed it in front of my mother. I thought of how, at five in the morning, my mother would throw tortilla after tortilla, and how my father dutifully carried bucket after bucket of drinking water to the house.

Reynaldo and Adriana were doing what they needed to do to survive. They respected and valued one another and chose to put their family before themselves. The woman I had seen as a slave to the stove now looked more to me like a strong mother with open arms, and the man I had seen as an overcommitted farmer now appeared determined and ready to carry the weight of his family’s burdens. I finally understood.

Anna Nafziger spent her SST in Nicaragua during the summer of 2014. In the fall of 2015 she will begin her fourth year of school at Goshen College, studying TESOL Education for grades K-12. She is currently spending her summer working as Assistant Program Director at Rocky Mountain Mennonite Camp in Divide, Colorado.

Anna Nafziger spent her SST in Nicaragua during the summer of 2014. In the fall of 2015 she will begin her fourth year of school at Goshen College, studying TESOL Education for grades K-12. She is currently spending her summer working as Assistant Program Director at Rocky Mountain Mennonite Camp in Divide, Colorado.