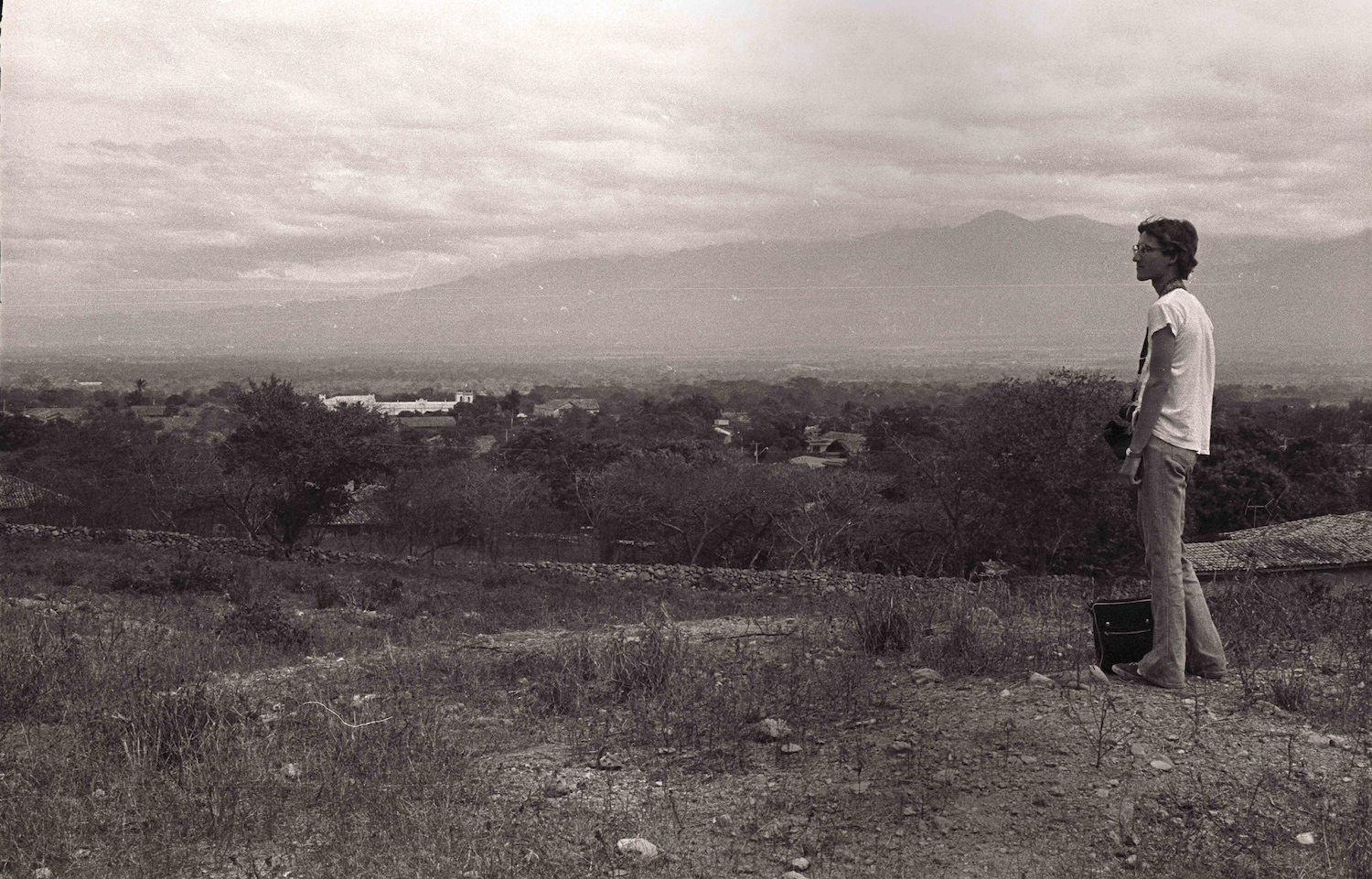

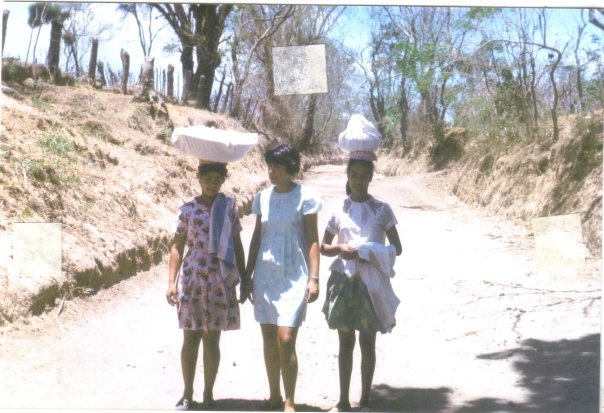

I was fortunate to be one of the first Goshen students to go on SST. Around 1970, I was part of the first SST group sent to Nicaragua. Fran and Marian Wenger were the leaders at that time. After our time in the capital, for my service project I was sent to the tiny rural village of Los Encuentros in the Dept. of Carazo. At that time the village had no running water or electricity and the only transportation was by ox cart. My hosts were the extended family of Pedro Rojas, and included his wife, his older daughter Luisa, his younger daughter Rosa, and her three children Julian, Albertina, and Maria Teresa.

My assignment was to encourage people in the village to contribute labor to build the first school, with the materials provided by the NGO CARE. I visited the families in the village to enlist their help. I also taught classes on a variety of topics to the local women and groups of children. Despite all my efforts during my term, I returned home feeling like I had had virtually no impact. I struggled deeply with culture shock and faced more questions than answers about my home culture and faith. I asked myself how a loving God could have afforded me such a privileged upbringing, and deny so many others the most basic necessities. Neither was I well physically. I suffered an extended bout with internal parasites, and my strength was slow to return. I remember it as one of the lowest times in my life.

As the years passed, I faithfully stayed in touch with my host family by letter, often writing them at Christmas and always hearing back. One year I remember sending Julian a small book encouraging him to learn English.

Many years passed. I was married to Cecil Graber and we were blessed with our daughter Sonia. Much later, in 1998, our daughter Sonia had just finished her own SST term in Costa Rica. It was then that we decided to travel back to Los Encuentros as a family, joining Sonia at the end of her term.

It was only then, some 25 years later, that I saw firsthand the “ripples in the pond” that my visit had helped precipitate. My host family killed a cow to eat in honor of my return, with the hide stretched out to dry upon our arrival. I learned that one women in the village had named her baby after me. And not only had the town completed the school we had struggled to build, but more buildings had been added on. In the school, they were still singing the little songs I had taught the children, now passed on by the same man who had learned them from me as a child. Julian himself was a grown man. Over the years, indeed he had taken it upon himself to learn English, continue his education, and go on to work for a variety of international development organizations. And the school that had enabled him to get an education had graduated many others who also went on to their respective professional pursuits. I was welcomed home that year to Los Encuentros as a daughter and I returned to the U.S. feeling for the first time that I had made a small dent in changing the world.

Our families continued to stay in contact through Facebook as years progressed. Then, in November of 2017, Cecil and I wanted to return again for an additional visit. The ripples in the pond had grown still larger. What amazed me was the full impact that my SST experience had had on Julian. Well educated, tech savvy, and connected in the international development community, Julian currently works for the US based NGO “Seeds of Learning.” His organization builds schools across the country in rural neighborhoods where there is still desperate need, multiplying the impact of the school in Los Encuentros that changed his world. Many students from the U.S. now volunteer with “Seeds of Learning”. At times they ask him, “How can you accept us in light of our country’s shameful legacy in Nicaragua during the war years?” Without dismissing that history, Julian also tells them the story of a young gringa who came to live with his family in Los Encuentros when he was only six. He recounts, “Susana helped us build our first school. She was such a loving and kind example of someone from your country who cared.”

I also learned during this visit that Albertina’s son Sebastian, now the 4th generation from Pedro, had just returned from Europe on a full scholarship to study there. And that Sebastian is currently a coordinator in Nicaragua of “Bridges to Community,” another organization committed to building schools.

Before we left Los Encuentros the last time, Pedro told me, “I can die happy seeing you again and knowing you have a good husband!”

Susan (Yoder) Graber is a retired preschool teacher from Eureka, Illinois, where she works as a volunteer at the Etcetera Shop and attends Roanoke Mennonite Church. She spends winters in Tucson, Arizona, and also frequently visiting her daughter in Denver, Colorado.