The Early Years series offers a glimpse into SST’s rich history through interviews with key players in SST’s creation and beginning decades. Part I was with Hank Weaver, who was on the planning committee for SST. For the second installment, we spoke with Norman Kauffmann of Goshen, who spent years studying the effects of SST on students for a dissertation and book.

Norman Kauffmann had never been abroad. When he came to the city of Goshen in 1969, SST’s first students were just unpacking their suitcases. No one could predict what the trips would bring. Kauffmann hadn’t even heard of the program. But by the time he retired from his position as dean of students in 1997, he was an expert in cross-cultural experience – as both a leader and an author.

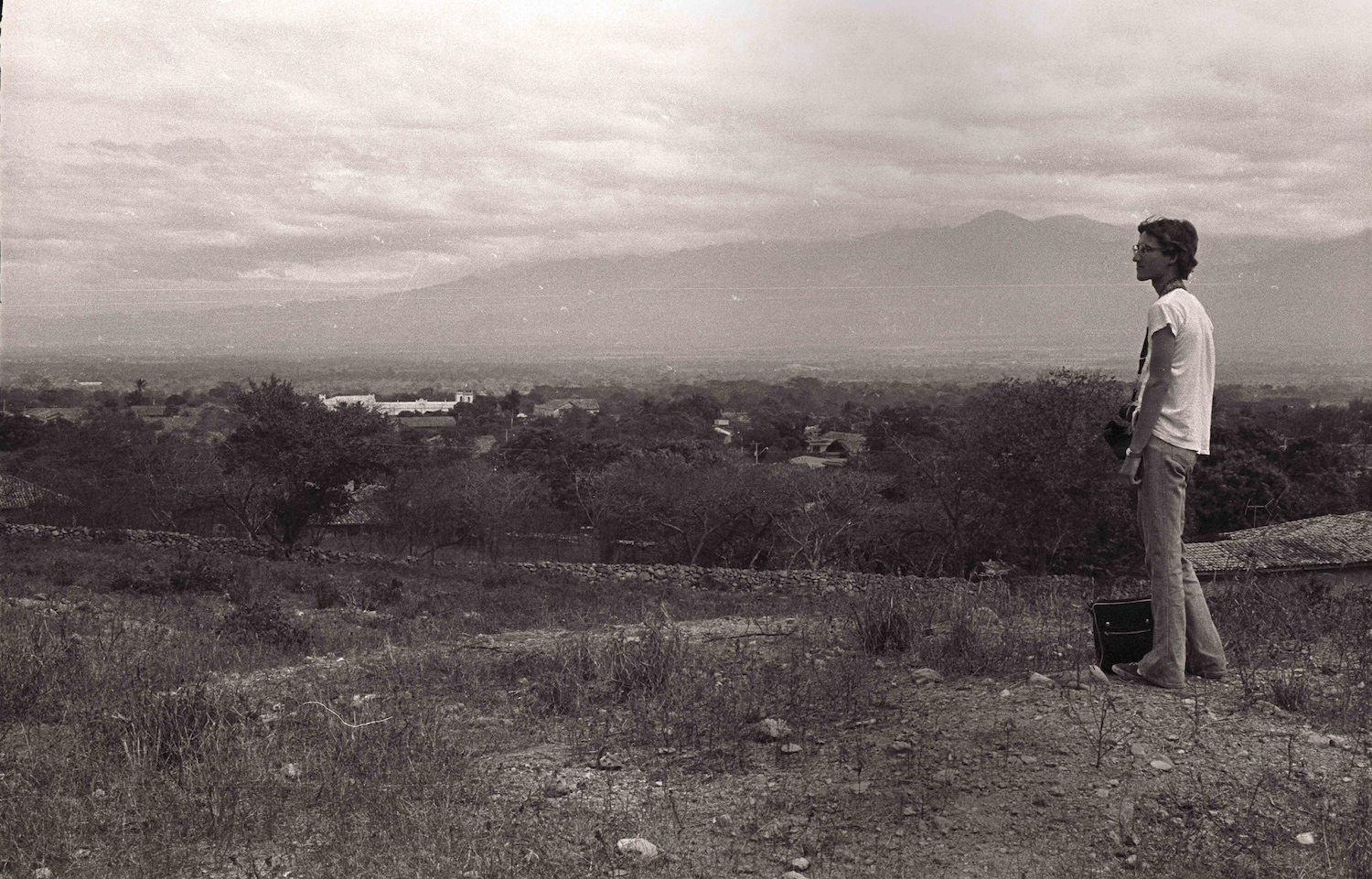

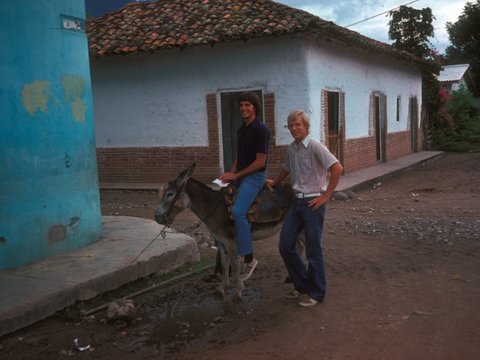

Each semester, Kauffmann would watch groups of sun-burned, jet-lagged students arrive home from three months abroad and wonder what they were thinking. He observed they were different – often in monumental ways – but couldn’t pinpoint how. After he led three terms in Honduras, felt and experienced a new culture up close, his intrigue grew.

When he began doctoral work at Indiana University in 1978, a dissertation advisor suggested documenting the different ways a private Christian college and a state university changed people. Kauffmann would focus on change, he agreed, but not at home—he would study what happened when people left familiar borders.

The project, undertaken in the 1970s, and again in the late 1980s, measured the impact of SST through more than 100 interviews. Kauffmann wanted to determine how students changed, and what fostered that change. Students took surveys before they left and after they came home; faculty, including Kauffmann, conducted longer interviews. A year after return, Kauffmann spoke to students again. Controls groups were Eastern Mennonite College, Bethel College and Bluffton College, which conducted study abroad on a smaller scale.

The dissertation led to Students Abroad, Strangers at Home: Education for a Global Society (1992), a book co-authored with Henry (Hank) Weaver, Judith Martin and Judy Weaver. Hank, a former faculty member, taught at University of California, and surveyed his students in comparison to Goshen. Martin did the same at University of Minnesota. The book focused on personal development, cultural immersion, and how change happens as a result of the study abroad experience.

When Kauffmann’s advisor read his dissertation, he was in disbelief that faculty members would serve as leaders – that would not have been possible at Indiana University, he said. Kauffmann considered it a privilege. He went back multiples times to visit friends he kept in touch with. His daughters became fluent in Spanish. He felt very close to his students, and was so glad to know deeply a smaller group on campus. He didn’t just study the effects of change; he was changed, too.

“Those of us who lived the program didn’t understand how unique it was until we started talking to other people,” he said. “You couldn’t always name its value, but I knew the program needed to be documented. It wasn’t just a dissertation for me—it was doing something worthwhile.”

After years of study in the 1980s and early 1990s, the results revealed a unique set of adaptations.

Students learn to see themselves as citizens of the world, not citizens of a country.

How, exactly, do students change? Each individual was different, of course, but Kauffmann recognized some broad patterns across the board.

- Many began to see themselves as belonging to part of a world culture, rather than just a U.S. one. Issues of social justice and interpersonal relationships became more apparent and more important.

- Self-confidence grew, in part because students ventured out of their comfort zones and learned to adapt in different ways.

- Value systems were altered in terms of faith and career; some students experienced a career change influenced by new perspectives from SST, switching to global issues or social work to find a major that would make the most impact on the needs they had witnessed, while others felt their vocation solidified.

- Almost everyone said they were altered by the hospitality, love and acceptance they received, often from poor families who had little to give—but gave what they had. Students were overwhelmed by the kindness they received, and had learned to love people in richer, deeper ways.

Location matters.

The greater the difference in culture and the higher the level of poverty, the more people changed. The interviews not only measured students who didn’t go on SST (Bethel, EMU, Bluffton) up against Goshen students, but also measured the differences between cultures. Those who went to westernized countries such as Germany didn’t make the same changes as those who went to more impoverished countries like Haiti or China, even though the programs were organized the same way with host families and a service portion. Many universities’ study abroad programs in the 1980s did not include language immersion, host families, service projects, or intermingling with people who had been made poor. Each of those factors created more room for change.

Self-aware students learn more about the culture; less mature students learn more about themselves.

Kauffmann used models of stage development theory, and found that students who identified as less mature felt greater change on a personal level, while students with increased self-awareness gained more in terms of intercultural growth. For students in the midst of an “identity crisis,” SST gave some time to figure themselves out, to understand themselves in new ways. Others who had a better idea of themselves were able to observe more of the culture.

Reentry is often more challenging than culture shock.

The students Kauffmann spoke to were very eager to be interviewed. Most coming back needed to talk about their experience, and some of their frustration was that families didn’t understand what their lives have been for the past months. It’s hard to know who to talk to and how to deal with those feelings, hard to readjust in a place that expects you to be the same when you feel different—particularly, Kauffmann found, when students came from wealthy families.

While Kauffmann’s research was conducted several decades ago, his findings are still an important exploration of how study abroad can affect an individual’s life and change everything from mindset and career path to faith and value systems. Travel abroad can teach you to be more open to difference or bring about greater self-awareness. It can solidify what you already thought or completely revolutionize what you believe. Everyone responds in different ways, Kauffmann found, but SST, without questions, changes people—in small and significant measures.

Global travel is more common today, Kauffmann said. There are many students who go on SST that are well acquainted with other cultures, who have gone abroad with their families. People study international economics and international business. The world, for some, is much more intertwined through technology and travel abilities. But there’s not any less need for global education – there’s more need, in part because of this increased connection.

“Study abroad is foundational, “ Kauffmann said. “And Goshen still does it in a way that no one else does.”

Read more about the changes Kauffmann found in The Impact of Study Abroad on Personal Development of College Students.

Norman Kauffmann began at Goshen College as director of residence life in 1968 and later was dean of students until 1997. During that time he led three units in Honduras (1974, 1984 and 1989). He received his doctorate in higher education from Indiana University, and his dissertation, The Impact of Study Abroad on Personal Development of College Students, studied the specific effects of SST. He is the co-author, along with Judith Martin, Henry D. Weaver and Judy Weaver, of Students Abroad, Strangers at Home: Education for a Global Society. He resides in Goshen.

Norman Kauffmann began at Goshen College as director of residence life in 1968 and later was dean of students until 1997. During that time he led three units in Honduras (1974, 1984 and 1989). He received his doctorate in higher education from Indiana University, and his dissertation, The Impact of Study Abroad on Personal Development of College Students, studied the specific effects of SST. He is the co-author, along with Judith Martin, Henry D. Weaver and Judy Weaver, of Students Abroad, Strangers at Home: Education for a Global Society. He resides in Goshen.

Kate Stoltzfus is co-editor of the SST Stories Project.