On a hot afternoon in Olanchito, Honduras, I walked back on the dusty streets from the edge of town after my last home visit for the day. I loved my SST service assignment teaching adults in a banana plantation town how to read and write. I would visit their homes several times a week for an hour or two of tutoring in Spanish.

One of the families had four students: Senora Alvarado and her three oldest daughters. The visit would last the entire afternoon, and I treasured our time together. Senora Alvarado lived in a very small, one-room cabin with her 13 children. We always had our lessons on one of the benches outside the house, as all the space inside was taken up with hammocks and cots. I had never been invited inside, but I could see those hammocks through the cotton curtain that covered the doorway.

Her cooking fire was outside, and every day she would prepare strong coffee for me from freshly roasted beans. It seemed that coffee beans and bananas were all they could afford. It didn’t occur to me until much later while in medical school that the explanation for the blond hair and protruding belly of her youngest child was malnutrition.

The Alvarado family was always so effusively grateful for the opportunity I was providing them to learn to read. Over the six weeks of our lessons together, I could see how happy they were to begin to be able to read some of the words in the hymnbook at the Baptist church they attended with my host mother’s family. Because my host parents had been educated and owned a small grocery store, their financial and social standing was much more secure than that of my students, who picked bananas or worked as maids or caretakers in larger houses. Senora Alvarado hoped that learning to read and write would open up more employment opportunities for her big family.

But as I walked home late that afternoon on the hot dusty lane, I could only think about how long the hairs on my legs had grown. In my first month in Tegucigalpa, I had noticed that none of the Honduran women, rich or poor, shaved their legs. After a few weeks, I thought I would follow local custom, simplify my life and let the hair grow.

But a month into the second half of SST, the hot breeze was moving the hairs on my lower legs back and forth so vigorously that they felt like tree branches waving in a thunderstorm. When I got back to my room, I didn’t even wait for a shower. I just dug out my razor from the bottom of my suitcase and sawed off those trees. Now I felt like a real woman again! Hmm…in my haste, there were quite a few scratches, some of which bled for a few minutes and formed some scabs. Oh well…

The next day, Senora Alvarado greeted me warmly, with a cup of strong coffee as usual. But then she bent over to look closely at my legs, and quickly called to her oldest daughter. You can imagine how mortified I was to hear her shout, “Alejandrina! Come here! Look at how much our teacher suffers for us! She even walks through thorns to get out here to teach us how to read and write.”

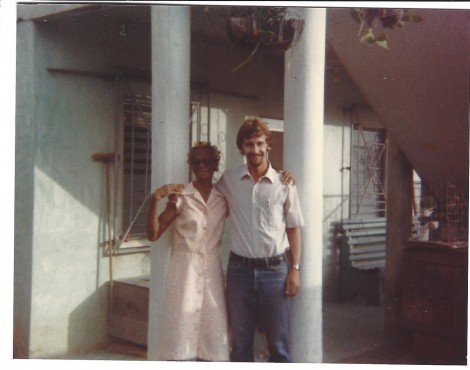

Norma Wyse spent the winter of 1973 teaching adult literacy while on SST in Honduras, majored in sociology and graduated from Goshen College in 1975. She attended medical school at the University of Chicago and then at UCLA, where she specialized in internal medicine. She spent several years studying medicine in Japan, teaching English to medical students in Tokyo, and raised two children. She currently teaches English to Honduran and Guatemalan immigrants in Waltham, MA, and serves on the Worship & Planning Committee of the Mennonite Congregation of Boston.

Norma Wyse spent the winter of 1973 teaching adult literacy while on SST in Honduras, majored in sociology and graduated from Goshen College in 1975. She attended medical school at the University of Chicago and then at UCLA, where she specialized in internal medicine. She spent several years studying medicine in Japan, teaching English to medical students in Tokyo, and raised two children. She currently teaches English to Honduran and Guatemalan immigrants in Waltham, MA, and serves on the Worship & Planning Committee of the Mennonite Congregation of Boston.

Top photo credit: Kristin Klein, Flickr