The children stopped to stare at the green truck as we passed. Our eyes locked: mine memorizing their angled arms and milky palms, theirs taking in my strange, thin hair and pale skin. Their mothers picked their way along the uneven ground at the side of the road, balancing wide ceramic bowls, eyes steady and careful.

After six weeks of study with the other SSTers in Abidjan, the largest city in Côte d’Ivoire, we were all heading au village. My destination was a tiny village beyond Danané, close to the western border of the country. I sat in the front seat of a Chevy pick-up, smashed between Charles, a Baptist pastor in Danané, and Lydia, his wife. Their children rode in the back. It wasn’t very far, but not knowing what lay ahead, I wished the drive would last forever.

The road was full of potholes and ruts, losing ground to the thick green vegetation. Some puddles were as long as the truck.

“The name of this village is Bougle,” Lydia said.

“Boo-gu-lay?”

They laughed. “Bwug-lee.”

I repeated it over and over until she nodded, smiling. Bougle’s buildings were white-washed mud huts with packed dirt floors. Chickens ran loose in the road. An old woman sat bare-breasted on a low stool in the shade. She stared as we passed.

…

The farm on the far edge of Bougle was an experiment in best practices. There was a fence to keep the sheep from wandering away, coops for the chickens, an orange grove, and buildings of hand-made brick. When it rained, my host father Alphonse, the farm’s owner, wore a pair of black rubber boots left by a Mennonite Central Committee volunteer.

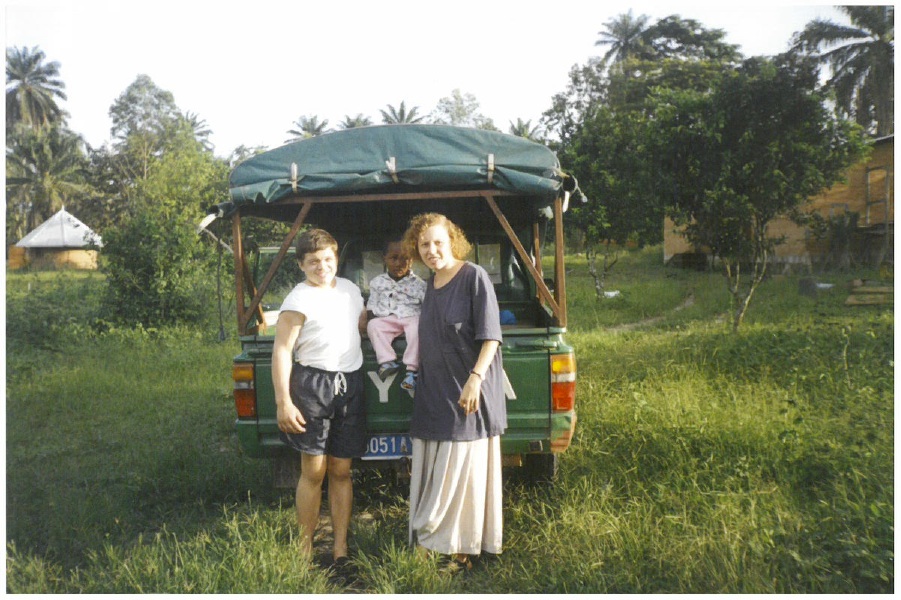

Alphonse gave me a tour. He loped tall and thin ahead of me, but he kept his French slow enough for me to understand. I’d heard part of his story before I’d arrived. His wife died in childbirth; at thirteen, his only daughter had died. Now he was married to Charlotte, who was only a year older than I was. They had a two-year-old son, Desiré, and Charlotte was in the third trimester of pregnancy.

…

I carried Desiré on my back as we walked the paths from the house to the field where the sheep grazed. I was babbling in mixed English and French. We followed butterflies. I pointed to them, and Desiré paid attention.

“Papillon,” I said.

“Pap-yon,” he hollered, grabbing at their fluttering bodies.

I bounced him as we walked. Charlotte and her younger sister Lea could tie him to their backs with a brightly-printed cloth pagne and somehow he stayed put, but I could never get the knot tight enough and settled for holding him up with one hand.

My project on the farm was to help develop a new strain of orange trees by crossing a native sour orange variety with a sweeter one. Now the seeds were germinating, and all I could do was wait.

Desiré’s body was draped against me, his little hands patting my skin. Alphonse worried about Desiré learning to talk now that his parents and I spoke French together rather than the Dan language they spoke to him when they were alone. He was afraid Desiré would be lost in the jumble of words. My French was sketchy and rough. I taught him to roll his r’s excessively. “Rrrrr,” we’d growl at each other, laughing and laughing.

He was my favorite companion, the only one who didn’t judge my awkward language. I wanted him to remember me. I wanted him to have a few words that he always pronounced badly just like me.

…

During siesta, I read: Maya Angelou, Alex Haley, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker. I underlined things and made notes in the margins. I memorized poems and repeated lines of them under my breath all day long. When Alphonse realized I didn’t have a Bible, he loaned me one in English. The familiar New Testament verses made no sense, but I read the stories in Exodus over and over again.

…

After breakfast, Alphonse brought me a chicken cut open with its intestines exposed.

“My chickens, they are sick, and now this one is dead. Can you tell me what caused this?”

He knew I studied biology. I looked at the soft pink and white innards of the bird. I’d taken a course in microbiology the previous semester, but that classroom, with its stainless-steel tables and its step-by-step procedural guides, belonged to another world. I needed glass slides and a microscope, certain chemicals to fix and stain a sample. I didn’t know what the chemicals were called in French, and I was sure they wouldn’t sell them at the market. I could hardly remember the procedures I’d memorized for class.

“So there’s nothing you can do?” I thought he looked a little disgusted.

…

We ate supper in the shadows of the lantern. Insects, drawn to the light, brushed against our hands. We ate rice with various sauces. Sauce gumbo. Sauce grain. The dreaded sauce longue, the consistency of mucous. We drank water with spoonfuls of sour orange syrup that Charlotte made from the fruit whose seeds I’d removed. Cucumber and tomato salad. Pineapple, mangos, bananas for dessert.

As a treat, we ate popcorn coated with powdered milk and sugar. When a praying mantis crawled into the circle of light cast by our propane lantern, Alphonse captured the bug in his hand. He disappeared into his bedroom and returned with a pair of tweezers. “Look,” he said. I watched him squeeze the creature. I watched as it died and as a thin, blood-red worm writhed out of the insect’s body and twisted in the air. “This parasite is very poisonous,” he told me. “It could kill you.” He dropped it into the lantern’s flame. I watched the light sputter as the worm shriveled and burned.

…

Around the fire, Lea and her brother Leon would talk, and I would lose the conversation, letting the language wash over me while I watched the fire, the stars, the palm trees’ tall jagged shadows in the darkness.

Some days, I bit the palm of my hand and leaned my head against the mud-brick walls, crying quietly so no one would hear me. There were strange and stark risks here: bandits in the night, quiet parasites, gardens that didn’t produce enough. They were not fazed. But everything fazed me: news of the war in Liberia, the death of a sheep who raided a bag of uncooked rice, the overwhelming lack of the people I loved.

…

We visited Charlotte’s family in a larger village. The cramped ride in a minibus took all day. The village was like a dream I had once: thatched roofs of huts poked out of the foliage, emerald rice fields shone in the sun. A dirty woman fell at my feet, begging in a language I could not understand. I looked beyond her at Charlotte’s face. “Elle est folle,” she said. Crazy. I didn’t have any money to give her, but I understood that I was responsible somehow; the woman was counting on me. Her voice got louder as I shook my head. The whites of her eyes were enormous.

…

Charlotte’s brother Leon took me on a tour. We went to the far edge of town to the sacred grove. A red dirt highway passed by the trees. Underneath the road ran a stream, little more than a trickle. Leon explained that the section over the stream had collapsed repeatedly while it was being built because, the villagers said, the encroachment into the grove had displeased its spirits. They had demanded a human sacrifice in exchange. Now the bridge held.

“Who did they sacrifice?” I asked.

“A Liberian man. He was walking along the road at night.”

…

We were less than ten kilometers from the Liberian border. Refugees from their civil war had flooded Danané, swelling the city to three times its normal size. It was impossible to tell exactly how many refugees had crossed the Nuon River because they were absorbed into villages with relatives. They spoke English instead of French like the Ivoirians, but they were from the same ethnic group and knew the same first language. In Danané, some of the Liberians were rich: people from Monrovia who wore jeans and Reebok t-shirts—even the women. I was walking along the road when a Liberian man stopped me and we talked slowly and carefully in English. He said he wanted to go to America, like all the men. I wasn’t sure what the women wanted.

…

Charlotte took me to visit the rest of her family. We sat on low stools in the shade, and I was introduced in French. The rest of the conversation was in Dan, and I sipped my cup of water and watched their faces. There was an old woman, Charlotte’s grandfather’s first wife. She sat on a low chair with a back. She had crooked fingers like my grandmother.

I shook her hand and she smiled at me. She was missing some teeth, but her eyes were firm and she held my hand tightly. She said something quick and low as she looked into my face and laughed. Then she dropped my hand and began to talk about something else.

One of her sons had gone mad. He was possessed by spirits, and all the sacrifices his mother had offered were not enough to get rid of them. They took me to see him. He lay on his side on the dirt floor of his small hut, reading the Bible. One leg was stuck through a log which ran the length of the hut.

They hadn’t always kept him like this, but he had seizures, and sometimes at night he would get out and do bad things, they told me. I wondered if he had epilepsy like my father. He lifted himself up on one elbow when we came to his door. He smiled, and I smiled back. He was missing teeth like his mother.

…

Toward the end of the week, there was a big funeral for a man who had been a police officer in Abidjan. His body was brought back in a fancy coffin on a bus. The family emerged in pairs, all of them wearing matching outfits. As soon as they stepped into the crowd, they began to wail. Leon held Desiré on his shoulders so he could see. On the other side of the bus, a group of ragged children and a woman were also sobbing. Leon told me that they were paid to be mourners.

In the middle of the night, I woke to the funeral drums from the center of the village. I tiptoed outside with a flashlight. Far above the short, thick coffee trees, the stars spread across the sky. The dark village was seamless, a place beyond understanding, beyond disbelief.

…

It was my last week on the farm. Early in the morning, Desiré tapped at my door, whispering my name. We walked into the cool gray dawn. The grass was still wet, but we looked for papillons anyway and played pretend, arranging a table setting of leaf plates on the ground, adding pinches of dirt to stand in for rice. When the meal was ready, Desiré covered his eyes with both hands and prayed: “Mama, Papa, Lenae. Amen.”

At night, Alphonse and I watched the moon.

“In French,” he told me, “when there is no moon, they say it is dead.” The moon was a sliver in the sky that night, waning. A dying moon. Once Alphonse had found me standing in the middle of the path, facing up. He’d snorted. “Lenae, the African moon is going to steal your eyes.”

Here I felt like I was all eyes, seeing scenes in swatches of color I was unable to interpret. What I saw had no connection to my brain. I had to write it down to sort out later. I could not forget, but I could not trust the fragile electrical pulses of memory. My brain was a thing separate from me. This is not my home, it told me. This is temporary. This is not something I understand.

My heart was another matter altogether. It said, I want it all: this sky, this soft-skinned child, this tangle of twisting paths. Amen.

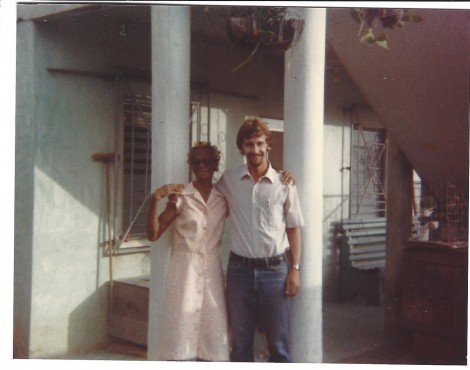

Lenae Nofziger went on the first SST to Cote d’Ivoire in 1993 and graduated from Goshen in 1994. After serving with Mennonite Voluntary Service in Seattle, she earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Eastern Washington University. Now an English professor at Northwest University, she specializes in creative writing and children’s literature. She lives with her family in Kirkland, Washington.