I had always known about the LANSA flight 502 plane crash on August 9, 1970 that killed 99 of the 100 Peruvians and Americans on board. I had always known about the flight that killed Albert Sarfert III, an eighth grader from New Jersey who had been participating in a summer study abroad program in Peru. I had always known about the flight that killed my mom’s brother, but it wasn’t until I went to Peru myself that I stumbled upon a tangible piece of my family’s history.

In the weeks before I left for Peru on SST, my mom showed me newspaper articles from the crash and pictures of a memorial site that was supposedly located (according to Wikipedia) on a mountainside near Cusco’s San Jerónimo district for the victims. Coincidence hit hard when I found out that our first portion of study was to take place in that very district. I knew no other specifics of its location, but it was enough to instill within me an incredible drive to find the memorial that no one in my family had seen, and gain a deeper understanding of the event that instantly changed the lives of my mother and her family.

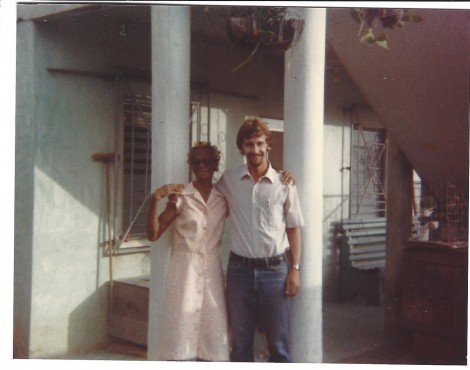

Upon arriving in Lima, I asked one of my fantastic leaders, Jane, if she had heard of a memorial located in San Jerónimo. She hadn’t. But during the first week of class we met Roberto, a local pastor who would occasionally lead class and join us on trips. Jane and I followed Roberto to the roof of our school in San Jerónimo, and he pointed to a spot in the distance. He told me that the memorial had once been located where he was pointing, but that he thought the land might have since been sold, the memorial relocated. Nonetheless, he agreed to meet me at the school on Saturday morning in hopes of tracking it down.

Our rainy walk up the valley lasted 20 minutes. Roberto stopped us as we passed his childhood house, explaining that the crash site had been nearby, and though he was only seven when it happened, he still remembered the day. Two farmers managed to pull the pilot out of the plane before it exploded; one of those farmers was killed and one was still living nearby. Many people collected the expensive items that were scattered across the valley from the wealthy Americans and Limeños, but they became frightened and returned them out of a powerful superstition. Local say you can still hear the ghost of a victim playing music at a nearby stream.

We ascended and there it was, in the backyard of an adobe house on a steep and muddy road: the tall stone cross, the wide base and the large plaque containing the names of the 99 victims. What had once been located on an isolated mountainside had now become consumed by expansion: a strange playground for the children and chickens who now lived there.

As I neared the memorial, I noticed a bird lying dead at the bottom of the cross. And to the right, among the other names, was my uncle’s name–though subtly misspelled–permanently engraved as it is in the hearts of my family.

When I returned home from seeing my uncle’s memorial that afternoon in Cusco, my host family warmly greeted me and took me to their chakra, where we picked alfalfa and talked about everything my limited vocabulary allowed. As the sun went down we retired inside the pink earthen walls of the house, sipping soup as my host brothers stared at me in admiration and my host parents taught me names of body parts in Quechua, their native tongue. Far away from home in an unfamiliar land, I had a new appreciation for history and a strange new sense of family.

My grandfather died about a month after I came home from SST with the comfort of knowing loved ones do return from Peru. Though death is permanent, pain need not be.

º

The fragility and ephemerality of life was a recurring theme of my Peru experience. Several weeks after viewing my uncle’s memorial, my girlfriend, Emma (now my wife) and I ended up at a quinceañera for a young girl with cancer. She was a classmate of one of Emma’s host relatives, and was celebrating early because she would not live to see age 15.

We did not know the girl at all; we were invited because we could sing and because we knew English, a language that the girl also knew and loved. Instead of bringing a journal to SST, I brought a ukulele, and though we felt very out of place, we offered imperfect songs to what was an emotional, awkward and powerful experience. The lyrics of a song I wrote after the party, “Quinceañera at Fourteen,” capture those feelings:

Oh how thin you are/with a face that outshines the stars/A quinceañera at fourteen/’You’re the luckiest/think all the younger girls who aren’t dying anytime soon/And we watched you dance to the moon with your father’s hands/and a brace to catch your swoons/ The rhythm’s long and it’s slow/ ‘You’re the strongest’/oh think all the older ones who don’t see you at night/

And your dress, a waving flag/Wash it in cold water, don’t let it fade/ do you mind if we laugh?/If you’re up to it, you should join in, too/It’s just the silence is getting a little weird/And I’ll sing to you in English ’cause I heard you think that it’s pretty/though I’m not exactly sure if it was your wish/but it’s all I’ve got to give right now/oh it’s all I’ve got to make sense of right now/

While traveling, I documented these impacting events and feelings through song and brought home a collection of 10 tunes, including “Quineañera at Fourteen.” You can hear the full album at Bandcamp.

Phil Scott is an 2014 alum and teaches elementary art in Goshen, Indiana.

Phil Scott is an 2014 alum and teaches elementary art in Goshen, Indiana.